Everyone is an artist! Or: Art as Prototyping.

Apparently, humans have always been concerned with art. But how does this fact fit in with our current practice, a practice that distinguishes between artists and non-artists (i.e., spectators, listeners, audience)? In the following text, I develop a philosophical argument for Joseph Beuys' claim that "Everyone is an artist!" and argue that it would be helpful to abandon this distinction and turn - as actively as possible! - to the arts.

The following text is the abridged version - a kind of extensive abstract - of a longer text available here: Kunst als Prototyping (PDF)

1 Preface

"People nowadays think that scientists exist

to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to give them pleasure.

The idea that these have something to teach them - that does not occur to them."(1)

How do we deal with art in our daily lives? Usually the audience keeps silent while the artist performs, paints or plays. Are we giving away potential in this functional distribution of roles? And if so, what kind of potential? To answer this question, I reconstruct in Section 2 Art as a Cult the widespread practice of sacralizing art. In section 3, Art as a Practice, I examine alternative approaches that have developed since the 1970s and which conceive art as a communal practice. In section 4 Art as a Dialog, I examine the extent to which philosophical conceptions of the human, such as those developed in philosophical anthropology, provide argumentative support for the approach presented in section 3. In section 5 Art as Prototyping, I draw a conclusion and suggest a further course of action.

2 Art as a Cult: A Critical Reconstruction

Where do we actually go when we enter a museum? We enter a special place, no doubt.

2.1 Places of Art: Museum and White Cube as Churches of Aesthetics

The idea of the museum is rooted in two powerful discourses of the 18th century. One is the emancipation and autonomization of art, the other the conflation of religious needs, reflections on art and literary theory, and critical insights of religion. Today, churches and museums show striking similarities, in some cases one even speaks of the museum as a place of ritual; the conception of the museum as a space of cultural practice has meanwhile also been adopted in contemporary exhibition practice.(2) (3) (4)

2.2 Objects of Art: Sacralization as a Local Convention

What is art all about? To answer this question, critics, essayists, and even artists often still fall back on a metaphysical hypothesis that originated in Romanticism and is the invention of a handful of thinkers. The specific reasoning is based on a series of misunderstandings and has long since been forgotten, but the theory is still alive and, for two reasons, has damaging consequences for our approach to art: Firstly, it hermetically seals works of art off. And, secondly, it deprives us of our pleasure in dealing with art. A reorientation in our thinking about and interaction with art therefore seems appropriate.(5) (6) (7)

2.3 The Mediating Tasks of Art: Proclamation, Education, Truth

Does art actually convey knowledge? There are different answers to this question. In fact, art does stand in a long tradition of didactic mediation, which, however, does not necessarily require exact representation. Nowadays, on the other hand, the concept of truth itself is in question; a workaround is art that no longer provides superficially correct answers, but instead raises questions to which the respective recipients must find their own responses. In this context also critical reflections about the role of public institutions and of education in general are on the raise, as well as discourses on what exactly is shown in a museum, why, and for whom.(8)

2.4 Protagonists of Art: Sacerdotal Precarity

Today most artists live and work in precarious conditions, despite the high prestige that is generally attributed to their artistic activities. Eventually this prestige, as well as the religious connotation of their acts or works (which derives from the above-mentioned metaphysical hypothesis), are motivational strategies that allow them continue their self-exploitation

2.5 Conclusion

Art is an area of where meaning is being created, an area where our cultures fabric is continuously woven by cultural practitioners, a web of significance that allows individuals to interpret their experiences and direct their actions. A web which they - as instinct-reduced deficient beings - necessarily depend upon. However, factually these webs of significance are developed under the exclusion of the broad public, a striking asymmetry of power that so far has rarely been taken note of and that has only recently been critically questioned..(9) (10)

3 Art as a Practice: Contemporary Experimentations

In many areas nowadays the way we approach art and culture is becoming increasingly free. Also new formats are evolving that better correspond to an updated and adjusted image of the human being and society as a whole. The result are new practices that enable individuals to develop their worldly orientation and self-positioning through self-expression and re-action.

3.1 Weltorientierung: Vermittlungsarbeit im Museum

Museums today have a precisely spelled out educational mission to which they respond as places of the authentic and the real, thus providing visitors with specific experiences. This kind of Art as Practice places high demands on those involved in the didactic and educational process: In addition to a strong orientation towards action, museum education concepts now also present latest research findings (e.g. from postcolonial studies). Thus, in the sense of John Dewey, they refer to a didactic of learning through concrete experience and doing.(11) (12) (13)

3.2 Self-Positioning: Emancipation within a Tension Field

Cultural education supports the individual in two different ways: It offers worldly orientation as well as self-positioning within the given world structure, thus pursuing approaches that promote both community and emancipation.

3.2.1 Community Music: Polyphonic Harmony

Community music is an example of community-building approaches in the arts. Here, pedagogical ideals such as inclusion, cultural and social participation, and social justice are given equal weight with musical (bottom-up) educational goals. The field is characterized by a high degree of interdisciplinarity at various levels (cooperation with other art forms, multidisciplinary teams). Community music has so far mainly been established in Anglo-Saxon countries, but is still largely unknown in Germany.(14)

3.2.2 Theater Work: A Balancing Act between Individual and Group

The emancipatory approach of arts education not only enhances a sense of community and belonging, but ideally also strengthens the individual himself so that he can confidently enter into negotiation processes with others. An example of artistic-pedagogical action that thinks democracy without a strict consensus orientation is Devising Performance, a format in which a theater piece is developed by the group itself and without any dramatic template. This form of radically democratic theater work questions certainties and power dispositives, it refuses to fulfill expectations and it demands a willingness to engage in debate. The internal structure of the group itself and the artistic result are related to each other, it is an artistic practice that thus also gains political relevance.(15) (16)

3.2.3 Protagonists of Art: The Artist as Coordinator

Projects like the ones mentioned above make high demands: Diversity, difference, maybe even dissent demand space, at the same time a communal artistic form should be conceived - despite all diversity. Protagonists who conduct such performative processes must be willing to withdraw themselves and leave the action to the participants. In addition to a high degree of sensitivity, pedagogical and artistic skills, this role requires also specialized knowledge to contextualize the emerging material culturally or politically, because only in this way can such work actually realize its full potential.(17)

3.3 Current Discourses in the Field of Art, Culture and Cultural Education

Current discourses in this field concern, among other things, Germany's particular historical situation and development, which continue to shape collaborative art forms and influence their reception until the present day. Another strand of discourse deals with considerations of justice theory, i.e., questions that concern the conditions under which inclusive, non-discriminatory access to cultural education and aesthetic experience can be guaranteed. Furthermore, the current debate explores the question of where to draw the line between art and social work. While social work has long had a cultural mandate, the now openly formulated social mandate of cultural work is relatively new. For politics, this results, in addition to the provision of financial resources, in the mandate to develop cooperative and sustainable structures for participation and steering. With regard to the project work itself, there is a considerable need for professionalization and research.(18) (19) (20)

3.4 Conclusion

Our approach to art has quite obviously changed, the art process has become dialogical, the focus has shifted from the artwork itself towards the process, a process that puts the individual at the center and has the potential to change the protagonists and even society as a whole. In addition to necessary structural adjustments in the sense of sustainable coordination and steering, the aforementioned changes should also be taken into account within the framework of scientific research projects and specific measures aimed at professionalization.

4 Art as a Dialog

Apparently, a paradigm shift is taking place in the way we interact with art. Art as cult and art as practice currently co-exist, but in some instances they have to face questions of legitimacy. These questions are for example raised by the phenomenon of non-visitors at cultural offerings. A similar phenomenon - offerings without users - currently exists within the medical system, which, despite its technically highly developed instruments, is increasingly confronted with patients that feel unheard by a system that cannot cure them due to a lack of empirical findings. How does the medical system deal with these challenges?(21)

4.1 From Knowledge to Action

Art as cult and art as practice are two different ways of looking at a single phenomenon: the phenomenon of art. Something similar - two different ways of looking at a single phenomenon - can be found in medicine. For a long time, medicine was regarded as a theoretical science concerned with general knowledge about disease; only recently has there been a shift within the self-perception of the medical profession, namely that of a practical science concerned with the singular individual case of a sick person. The consequences of this shift become apparent in psychosomatic medicine: The patient faces the physician's subject as an autonomous subject himself, any action becomes joint action, inter-subjective, inter-bodily, a cooperative-communicative process.(22)

4.2 Individual and Environment

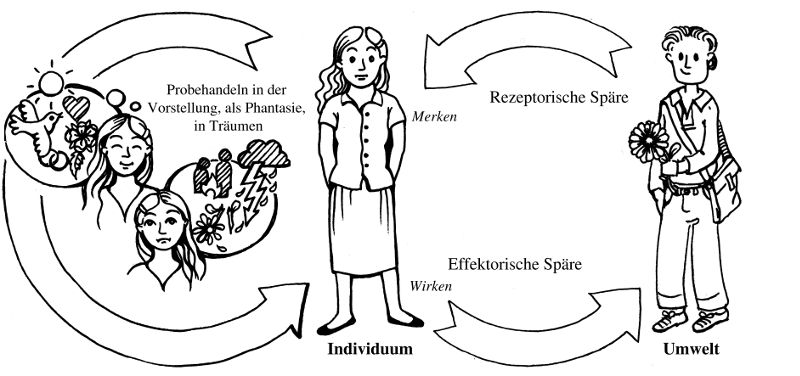

As we have seen, art represents a way of developing worldly orientation and self-positioning. One milestone within the bio-semiotic turn in human medicine, is the theory of the Situationskreis (situation circle). This theory deals with the question of how to conceive the relation between individual and his specific environment and states that factual acting in / dealing with the world is preceded by suggestion and attribution of meaning in the course of an imaginative rehearsal.

In this theory’s specific application in human sciences, three concepts that are well known in philosophical anthropology and phenomenology play an important role: matching ratio - responsiveness - mentalization.(23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28)

4.2.1 Matching Ratio

Matching ratio is a fundamental functional principle of living systems, its goal is the interaction of individual and environment in the sense of an interactive coordination process. If the coordination succeeds, this is - in medical terms – called health; if matching ratio does not succeed, symptoms refer to adaptation disorders. In this sense, the physician's task is to re-establish dialogue between the patient and his environment and thereby promote health.(29)

4.2.2 Responsiveness

Matching ratio can succeed when the individual is accessible, open, responsive. In this view symptoms are not signs of disease, but responses that, in the absence of responsiveness, unilaterally refer to the needs, desires, or expectations of the individual himself. Responsiveness is also described as a form of relatedness that shapes the living body’s entire behavior and presupposes the ability to perceive the needs and expectations of others in addition to one's own.(30) (31) (32)

4.2.3 Mentalization

The ability to mentalize gives the individual access to both his own and other people's reality. Mentalizing means grasping and understanding one's own and other people's behavior and experiences through the attribution of mental processes. In this way, through a metacognitive process, the individual is able to gain inner distance from events or experiences, and also to change perspective. The ability to mentalize is not innate, but develops during childhood. This process can be inhibited or made more difficult by unfavorable circumstances, also trauma can impair an already developed ability to mentalize.(33) (34)

4.2.4 Conclusion

Matching ratio, responsiveness, and mentalizing are the basis for the individual's successful interaction with his or her environment: Matching ratio refers to the successful matching process, which requires responsiveness and mentalizing abilities. Symptoms are indicators of maladjustment and, in any case, the organism’s best possible response with regard to its given possibilities.(35) (36)

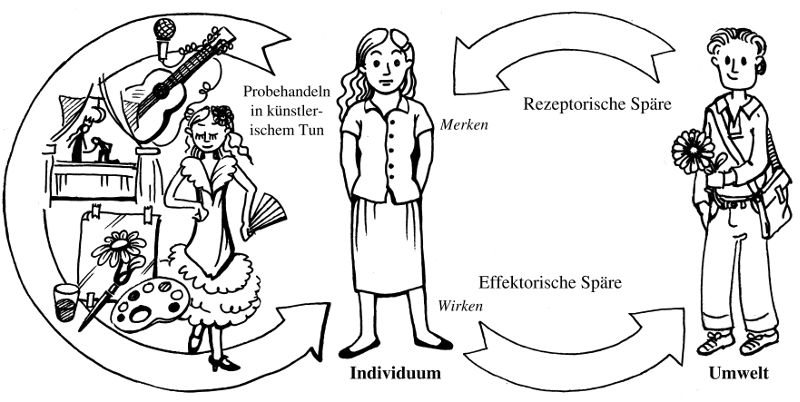

4.3 From Rehearsal to Prototyping

Art has a long tradition in the treatment of both bodily and psychological disorders. The aim of the most important institutional form of therapy, art therapy, is to explore one's own inner world, to open up new spaces for play and action within the protective space provided by the work of art itself, and to playfully try out new possible solutions - prototypes - in a tangible and thus understandable way.

In this sense, creating a piece of art is a rehearsal in concrete, factual action in three-dimensional space, often also with a inter-subjective dimension. Eventually the general effective factor that makes the artistic process a remedy lies precisely here.(37) (38)

4.4 Cracks and Holes in the Cultural Fabric

Our surrounding world is becoming increasingly confusing, and for many individuals the matching ratio is more and more fragile. A loss of matching ratio shows itself in symptoms of flight and struggle: withdrawal and isolation - or aggression, fundamentalisms, nationalisms. It is interesting to see that people who have suffered traumatizing experiences often are susceptible to seemingly simple solutions. The question that arises is: Does this happen despite these experiences - or perhaps precisely because of them? If a successful matching ration requires responsiveness and mentalizing, then traumatization is definitely a risk factor: Those whose ability to mentalize their own and other people's inner states, i.e. to grasp and understand them, is dramatically blocked by traumatic experiences, will find it difficult to open themselves responsively to the other in order to achieve a matching ratio in this way. In this case simple solutions like the various isms provide substitute structures: Crutches that allow the individual to laboriously, clumsily, and eventually destructively maneuver through his world.(39) (40)

4.5 Weaving the Fabric Anew

How can an intrapersonal, identity-forming web be re-created in those places where the matching ratio has been lost, where the cultural fabric of meaning has become fragile? Certainly not with the help of an obligatory Leitkultur - a German term demeaning guiding culture. Rather through personal experience, dialogical, polylogical examination, exchange, contact, joint action with other people, a process at the end of which, eventually, almost as a memory, a work of art emerges? A jointly developed prototype that testifies to the fact that those who have created it together have simultaneously recreated themselves...

4.5.1 First Cross-Linking: Responsiveness and Mentalizing

Responsiveness and the ability to mentalize are related in two ways: The precondition for individuals to develop the ability to mentalize is a responsive, empathetic environment. And only if they have acquired the ability to mentalize, i.e. to interpret their own and others' experiences and behaviors by attributing mental content, will they be able to respond responsively to others. Attachment insecurity and traumatization impair mentalizing and thus responsiveness.(41) (42)

4.5.2 Second Cross-Linking: The Artist as a Listener

Usually the audience listens to the artist, and it is easy to lose sight of the fact that artists are listeners themselves: Artists listen to their own inner selves, they are open to (external) partial worlds represented by the works they interpret, and they are receptive to the unitary reality underlying everything. In other words: Artists are people with special sensors, with fine antennas for foreign mental contents of a real or imagined counterpart. They share this ability with doctors, who in listening become co-constructors in their patients’ cognitive process, an aspect still too often overlooked.(43) (44) (45) (46) (47)

4.5.3 Third Cross-Linking: Art as Practice - as a Healing Process for Loss of Matching Ratio (a Disease without Diagnosis)

Art therapy, highly effective, widely used, little researched, has one serious drawback: It presupposes a diagnosis. What if the patient does not feel sick or there is no diagnosis for his suffering? Or what if the pathology does not manifest itself individually but in society as a whole? Who should be treated then - and how?

Humans are wonderful, but also highly fragile beings. Traumatization and its consequences have accompanied humanity for as long as there have been wars, natural disasters, and unhappy families. And for just as long there have been testimonies of healing, we guard and preserve them: in our museums, theaters, concert halls.

In uplifting moments, these works of art - Sophocles' Ajax, Picasso's Guernica, Beuys' Zeige deine Wunde, Bach's Chaconne, to name a few - still heal us today, making our broken lives whole again. So the system of art as cult does make sense. But it is not more than a makeshift in times when there is nothing else. For healing happens in community, in the Mitwelt (our environment, people, nature, things), in invocation and response, here and now, in-between human beings. By just being there. By being present, by participating. By having others listening to us while we are telling our story. By speaking out aloud, expressing, what we hear. By opening ourselves to the invocation through our own centric core. And by ascertaining ourselves eccentrically in processual, existential action and thus draw the boundary that transforms us from thing to organism and lets us find our way back from traumatized muteness to expression.

For all of this art provides a safe framework. All the great works of art were created here. They all speak of existential experience, pain, separation, injury, loss, death. Experiences that have silenced individuals. And of transcendence and rediscovered language in artistic expression.(48) (49) (50)

4.6 Conclusion

What is it that makes us human beings stand out? It is our twofold positionality, mediated by the ability to mentalize and to be responsive. The refinement of these abilities seems to have no limit, until they finally merge into the basic word I-Thou.

Considering their immeasurableness, we are invited to develop these abilities or, sometimes after painful losses, to revive them. For this endeavor art is a training area, a safe framework, a place where we can symbolically-symbolizingly find wholeness within the intra- or intersubjective dialogical process.(51) (52) (53)

5 Conclusion: Art as Prototyping

How can we answer the question posed at the beginning, whether we are giving away potential with the functional distribution of roles between a silent audience and the performing artist? If one takes seriously the conception of philosophical anthropology that man is an eccentrically positioned being and needs culture in order to find his balance, the answer is clearly: Yes!

Art and artistic activity offer a safe space for self-reflection, an activity that strengthens people in their individual so-being by enabling them to locate themselves through artistic activity within themselves as well as within the world - precisely the two positions of the human being, the centric and the eccentric. Quite obviously, this work must be carried out, albeit to varying degrees of intensity, by each individual independently because it is not possible - or at best only to a very limited extent - to delegate it to a third party, however well trained they may be.

From these findings suggestions for further action can be derived. For example, that of transforming the strict separation between artists and audience into a togetherness. Into a togetherness of humans who meet as humans in conversation at eye level and who work together artistically in an inter- or intrapersonal dia- or polylogue. For artists, who guide this kind of togetherness as an artistic intervention, this implies the need for professionalization, enabling them to conceive or carry out community art projects. And for philosophy as a discipline to develop argumentative structures of justification for already existing practices of community art and, moreover, to contribute in terms of content with regard to the often philosophical themes negotiated in art, which frequently are the existential questions of human existence.