I and You. A Reflection on the Relationship between Empathy and Art.

How is it possible that a work of art touches us? I am an artist - of course I am interested in this question. A first trace may be found in the phenomenon of empathy, the human ability to empathize with another person, to "feel what the other person feels". But is empathy limited to that, to just feeling what the other person feels? Or could empathy perhaps be more that that, more specifically: a kind of communication channel open in both directions?

1 Preface

"On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind."(1)

James Rhodes quotes the above passage in his book Instrumental. And he quotes it in a decisive passage: When, in a situation of deepest despair(2), he finally draws hope. When he sees his personal silver lining on the horizon, in the form of Bach's Chaconne.

How is it possible for a work of art to develop such power? The power to change a human life, to give hope in a situation that can hardly be more desperate and hopeless?

And how is it possible for a human being, Johann Sebastian Bach, to create such a work of art? A modest existence, an artist who was forgotten when he died, and whose work was rediscovered only 80 years later.(3)(4) A titan, of whom Mozart says: "Bach is the father, and we are the boys. Those of us who are able to do something right have learned it from him."(5)

These are interesting questions. But it would be a presumptuous request to reveal this secret in its entirety on the following pages. Therefore the present work should only deal with a partial aspect of the mystery: How is it possible that a work of art touches a person, moves him deeply, perhaps even heals him?

2 The Hypothesis

So, how is it possible that a work of art touch us? The phenomenon of empathy might be a first trace, the human ability to empathize, to feel with another human being. The common understanding of empathy is that it enables us to "feel what others feel"(6). But is the phenomenon of empathy limited to that? If empathy is the ability that allows one person to, so to speak, eavesdrop on another person, like a doctor listening to a patient's heartbeat with the help of an instrument, a stethoscope, would it not be imaginable that that person, the eavesdropping person, could communicate something to the other one along the same path? And couldn't it be possible that the eavesdropped person eventually is receptive at the specific spot where the empathic stethoscope touches his being? In other words: Is our ability for empathy perhaps more than a diagnostic instrument, is it possibly a kind of channel of interaction between people, a channel, an ability whose degree of expression may vary from person to person, but which in any case enables communication?

Whether or not this hypothesis is tenable will be examined in the following, taking into account various current views on empathy. We hope that these theories about empathy will not only not contradict the possibility of conceiving empathy as a channel of communication, but may even contain elements that support this hypothesis.

And if this is actually the case, namely that empathy represents a channel of communication open in both directions, then this would possibly also shed some light on the question why, from the beginning of time, people have occupied themselves with such a useless thing as art: Because art is one of the most elementary building blocks of interpersonal contact.

3 What is Empathy?

3.1 Empathy and the Problem of Other Minds

As soon as we deal with empathy, we come across one of the unsolved basic questions of philosophy: the Mind-Body-Problem, established by Descartes with his strict separation of body and mind. If we follow Descartes' agenda, we are immediately confronted with insurmountable epistemic rifts, not only between our own body and stream of consciousness, but also the fact that only I myself have access to my stream of consciousness - and nobody else. The latter is known as the Problem of Other Minds, and lays down that no one has access to the psychic contents of any other person.(7)

Of course, this view contradicts our ubiquitous experience that we, humans, are convinced to know quite well what our fellow human beings think, desire or feel. Empathy takes up this everyday experience and tries to explain it. The two, for a long time predominant theories are Theory of Mind or Theory Theory (TT conceives mental states as constructs/theoretical terms and makes predictions from the third person perspective(8)) and Simulation Theory (ST uses analogy from the first person perspective to the contents of another person's consciousness through creating this person as a kind of novel character within ourselves(9)).(10)

The basis of these two theories, TT and ST, is, as already mentioned, the Cartesian separation of body and mind. However, this is precisely what at the beginning of the last century has been called into question by phenomenologists(11) who perceive the human body as a living body:

"The world in which I live is not only a world of physical bodies, there are also subjects who experience it besides me, and I know about this experience. [... The sentient] body to which an ego belongs, an ego that senses, thinks, feels, wants, whose body is not only part of my phenomenal world, but which is itself the center of orientation within a phenomenal world which it confronts while interacting with me"(12)

Both, (physical) body and mind, thus form a unit of expression: the lived body. If one follows this thought, then, in order to find access to the inner states of our counterpart, it is sufficient to look at his lived body. We therefore need neither theoretical terms nor an inner simulation.(13)

As a consequence, Interaction Theory (IT) has developed. What fundamentally distinguishes IT from TT and ST is the second person perspective, which closes the Cartesian divide between body and mind, lived body and soul and thus removes the epistemic basis of the problem of other minds. IT does not dissolve first and third person perspectives but integrates them: A shared, joint experience from the first-person perspective remains possible, as does an observing distance (third-person perspective).(14)

3.2 Empathy as a Diagnostic Tool

Kohut describes empathy as "a mode of perception especially attuned to complex mental configurations"(15), which focuses on collecting (but not ordering and analyzing) mental facts and is as such the only adequate approach to this area.(16)

"One can rightly say that one of the particular contributions of psychoanalysis is to have transformed the intuitive empathy of artists and poets into the instrument of observation of a trained scientific researcher, although judgments of experienced psychoanalytical practitioners to the observer may sometimes seem just as intuitive as the diagnoses of an internist, for example"(17)

With regard to psychological facts and in the scientific context, prerational-intuitive empathy as a method of collecting and rational-discursive analytical process complement and fertilize each other. Moreover, one without the other threatens to become either fact-rich irrationality or sterile-mechanistic subtlety.(18)

Kohut conceives empathy above all as a diagnostic tool or, otherwise put, as the adequate access to the human psyche. In his opinion, empathy is by no means a curative drug that, by itself, can alleviate any suffering.

"They will claim that empathy cures. They will claim, that one just has to be 'empathic’ with one's patients and they'll be doing fine. I don't believe that at all. [...] I would say that introspection and empathy should be looked at as an informer of appropriate action. [...] These purposes can be of kindness and these can be of utter hostility."(19)

3.3 Empathy and Morality

So far we have seen that empathy is the ability to gain insight into the psyche of another person. That empathy opens up a kind of connection channel through which one person can collect information about another person, which may be processed further and result in actions. However, empathy does not determine in any way the nature, intention and quality of the resulting actions.

This contradicts the widespread notion that empathic people, people who can empathize with others, make our world a better place. The logic behind this is simple: Who would voluntarily inflict suffering on another person if he could understand how terrible it feels? More than once Barack Obama has thus consistently diagnosed the Western societies' apathy in the face of the countless armed conflicts in the world’s crisis regions as a "lack of empathy".(20)

However, studies have shown that this intuition does not yield enough. People with a heightened capacity for empathy are particularly likely to help those whom they perceive as similar to themselves: Instead of having compassion with everyone, they show compassion with their peers (ingroup-favoritism). Increasing empathy does not automatically lead people to behave morally, nor does moral behavior require the ability to empathize.(21)

What actually promotes moral, impartial, pro-social behavior, on the other hand, has only indirectly to do with empathy as an ability of feel what others feel: It is spiritual exercises such as for example Buddhist Mettā-Meditation(22)which help to widen our view and the circle of beings which matter to us. The fact – which has already been empirically proven – that we as well benefit from the positive effects of such an attitude, can eventually be explained by the circumstance that a practice of greater compassion towards all beings also includes ourself among them.(23)

3.4 Empathy as Joint Embodiment

Above we were taking a close look at Interaction Theory, an integrative overall concept which understands the human being as a unit of expression, with a living body that comprises (physical) body and mind. In addition, IT integrates first and third person perspectives within the second person perspective and makes individual experience simultaneously a shared and a common phenomenon.

But what exactly happens when two people are physically present and connect in the aforementioned way, as living bodies that meet in the second person perspective and become part of something collective, of a joint process? There are complementary explanations for this kind of - as Merleau-Ponty calls it - intercorporeality, such as enactivism(24) and the concept of mutual incorporation (joint extended body).(25)

3.4.1 Enactivism

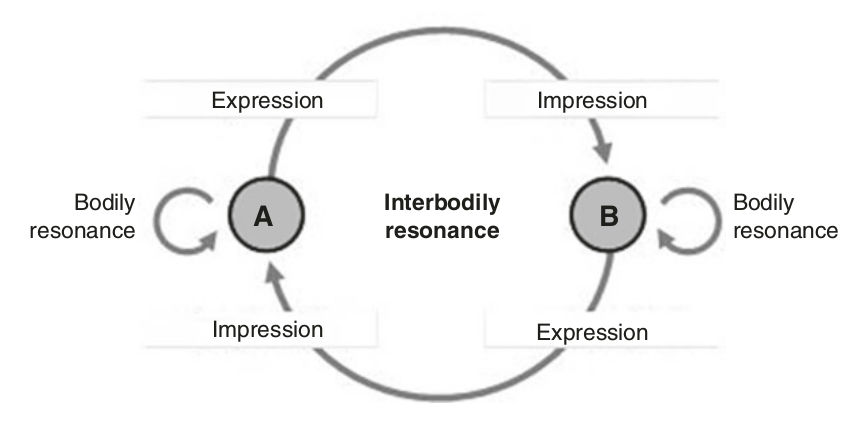

According to enactivism organisms do not just absorb information from their environment but also interact with it, which in turn makes the environment a product of this interaction. In this sense, social interaction and consequently social cognition can be seen as a circular process between two agents consisting of multiple perception-action feedbacks: Adjustment of postures, facial expressions, gestures, rhythm and speed of speech, common focus on an object, etc.(26)

Normally, this joint process takes place without any agent's conscious control - because he himself is part of the dynamic process. However, within the framework of joint interaction, each agent develops increasing skill in functioning within the joint process, a skill that developmental psychologists call implicit relational knowledge.(27)

3.4.2 Mutual Embodiment

As we have seen, the circular process of perception-action feedback interconnects the two agents. However, this does not happen through coordination of their brain states, but in the form of a common, dyadic body state of two responding, embodied subjects. In this sense, contents, such as the emotional state of one agent, become accessible to both agents: for one agent as a direct emotional experience and for the other one as a direct experience of a more or less intense reaction to this emotion.(28)

If we take another step back and recall how knowledge is generated within the framework of enactivism theory, then the living body, as an agent interacting with its environment, plays a decisive role in the genesis of knowledge:

"According to the paradigm [embodied cognition paradigm in cognitive science; KUS], the body plays a constitutive role in cognition, that is, cognition depends directly on the body as a functional whole and not just the brain. [...W]hat is meant by 'body', for the enactive approach, is [...] the body as an adaptively autonomous and sense-making system."(29)

The interconnected bodies - Fuchs calls this state "mutual incorporation"(30) - thus generate knowledge by interacting with each other:

"In every face-to-face encounter, our bodies are affected by the other’s expression, and we experience the kinetics and intensity of his emotions through our own bodily kinaesthesia and sensations. Our body schemas and bodily experiences expand and incorporate the perceived body of the other."(31)

Mutual embodiment of two agents is here a kind of extraordinary coincidence, the special case of a phenomenon that is omnipresent in our everyday life. If, for example, we skilfully handle an instrument (a blind person's cane, a piano) or let ourselves fall under the spell of a high-wire circus artist, then we, so to speak, merge: in the first case with an object, in the second case - albeit in a one-sided way - with another human being.(32)

Neither the object nor the other person with whom we are unilaterally coupled in this way will be influenced by our reaction, although at least the high-wire circus artist may perceive our reaction. The object will remain an unchanged object, the high-wire circus artist will continue his presentation uninfluenced by our reaction(33). Only the other person, with whom we find ourselves in dyadic, reciprocal embodiment, enters into resonance with us: What he triggers in us becomes visible for him through our body, he can experience it and allow it to trigger his own reaction to it:

"This creates a circular interplay of expressions and reactions that occurs in split seconds, constantly modifying each partner’s bodily state. The process becomes highly autonomous and is not directly controlled by either of the partners. They have become parts of a dynamic sensorimotor and interaffective system that connects their bodies by reciprocal movements and reactions. Each lived body reaches out, as it were, to be complemented by the other; both are coupled to form an extended body through interbodily resonance or intercorporeality [...]."(34)

Our ability for empathic perception is thus twofold: On the one hand it consists in our ability to perceive our counterpart, on the other hand in the awareness of our own bodily reaction to our counterpart: "One feels the other in one’s own body"(35). However, usually the perception of our own body reaction recedes behind the perception of our counterpart (similarly to the self-perception of our finger which recedes behind the perception of the touched surface), only with one notable difference: The touched, perceived surface remains in its essence unaffected by our touch - unlike the human being, with whom we are, so to speak, mutually embodied in dialogue.(36)

3.4.3 Implicit Relationship Knowledge

But what about Interaction Theory in comparison to competing approaches like ST and TT? Fuchs puts forward a strong argument, namely that dyadic, reciprocal embodiment (and not theory formation or simulation) is a primordial human capacity since even infants are capable of making contact with their caregivers in this way:(37)

"Six- to eight-week-olds already engage in proto-conversation with their mothers by smiling and vocalizing [...]. Both caregiver and infant exhibit a finely tuned coordination of movements, rhythmic synchrony, and mirroring of expressions, which has often been compared to a couple dancing."(38)

In these early childhood experiences of mutual embodiment the infant will develop implicit relationship knowledge and interaction repertoire for dealing with other people, which he will use throughout his whole life:

"This prereflective knowledge or skill of how to engage with others includes knowing how to share pleasure, elicit attention, avoid rejection, and re-establish contact. [...I]nfants acquire special interactive schemes [...] and corporeal micropractices[. ...] It may also be regarded as interbodily memory that shapes the actual relationship as a procedural field, encompassing and connecting both partners.(39)

Obviously, the capacity for dyadic, reciprocal embodiment is deeply rooted in human existence. But to understand it purely as instrumental, as a method by which a partner deciphers the emotional states of his counterpart thanks to a common flow of body expressions, would fall short. At its core, mutual embodiment actually means much more: it is about joint embodiment and thus a common field of experience in which both partners participate.(40)

3.5 Conclusion

So what is the role of empathy now? Well, very fundamentally, we could say that

"On the epistemological side, it might be suggested that the role of empathy is to provide us with knowledge of the environment or, alternatively, of what others are likely to do [...]."(41)

Empathy is thus first and foremost - and this is probably an undisputed view - a diagnostic instrument: It provides us with information about our living environment, about our counterparts, and thus gives us the opportunity to function more effectively in the world and/or within a group of fellow human beings. Empathy thus represents a survival advantage, however, without directly promoting pro-social behavior per se.

Looking at Interaction Theory and the model of mutual embodiment, it becomes clear that empathy may not be an informational one-way road: Yes, we can use it to collect information about our environment and this information will provide us with survival benefits. But due to our own structure as enactive organisms, this information will in turn affect us and our own structure/state/system: it does not leave us untouched, on the contrary, it touches us and changes us in the process.

Perhaps this last point is the most disturbing one: That the individual is much more open, much less self-contained, and self-sufficient than we generally assume. We can easily integrate objects into our body-being (the blindman's cane, the piano, etc.). But this openness of our system works in both directions: We are also touched by our surroundings and, under this touch, in constant metamorphosis.

4 Thou and I

Our ability to empathize does not open up an informational one-way road; humans are rather enactive, living organisms that are in continuous interaction with their environment.

4.1 Various Forms of Embodiment

Within the framework of Interaction Theory, empathy can probably be understood most coherently as reciprocal incorporation:

"Now, mutual incorporation implies a reciprocal interaction of two agents in which each body schema extends and embodies the other."(42)

Mutual incorporation however, represents a special case of the phenomenon of embodiment. Embodiment - the merging of our living body beyond its physical limits - is familiar to us as an everyday experience (the use of an instrument; our fascination with the performance of an artist).(43) But not every embodiment, as we have seen above, is equally reciprocal:

...with an inanimate object | ...with a living organism | |

One-sided incorporation... | Instrument (e.g. cane for the blind, piano):

| Artists (e.g. high-wire circus artist): going along, experiencing third-party contents of consciousness without feedback within the counterpart |

Mutual embodiment... | - | Other human beings: multiple perceptual-action back couplings |

Tab. 1: Forms of Embodiment

Source: Own Design

Mutual embodiment is therefore - if at all - only possible with animate organisms.

And there are obviously very different degrees in type and intensity of the respective feedback from animate organisms.

The standard case that Fuchs uses as a departure point is mutual embodiment of similar agents:

In Fuchs' example, A experiences strong emotions, which also manifest in his body and in turn make his body, so to speak, the sounding board of his feelings. B not only perceives these physical signs, the physical expression of A's emotions, but also reacts to them physically. B therefore perceives A's emotional state not only visually on A's body, but also through the reaction of his own body.(44)

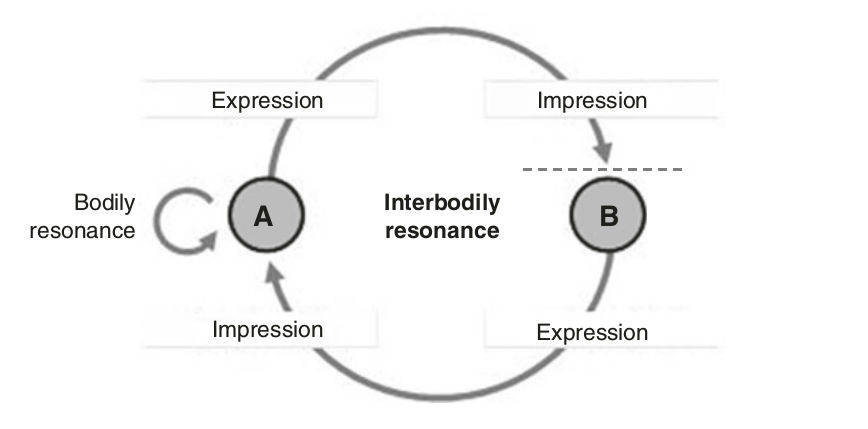

However, this cycle of perception-action feedback can also be interrupted, for example when a spectator observes a high-wire circus artist performing a dangerous trick(45):

In this second case, the high-wire artist B creates feelings (for example fear, excitement, tension) in spectator A through his trick, i.e. an impression to which A reacts physically. The physical reaction of A to these feelings (for example the sudden silence in the circus arena, hundreds of spectators holding their breath, an almost tangible tension) is very likely to be perceived by B. But - and this distinguishes this case from the previous one - B at the same time is able to keep his own physical reaction to a minimum and instead to continue, relatively unaltered, his feat, his own expression. B thus affects A, but without letting himself be affected by A's reaction.

The fact that during the process of mutual embodiment A and B both enter into a perceptual-action feedback and both change correspondingly during this process is the normal occurrence in living organisms. However, the fact that B - the high-wire artist from the second example – is capable of maintaining distance and, although A resonates with him, even contrary to his own nature as a living organism, continues his expression unaffected by A's reaction, represents, in a sense, the special case of the special case.

4.2 Controlled Mutual Embodiment

This special case of the special case - let's call it controlled mutual embodiment - is thus characterized by the fact that one of the agents is able to elude his own nature's striving for perception-action feedback with his counterpart, i.e. to control the natural reaction of his own living body to its environment.

For it is precisely this part of the natural tendency towards mutual embodiment, the evenly meandering flow of perceptual-action feedback between two agents, that is an obstacle when it comes to actually using empathy as a precise diagnostic tool, as Kohut demands of the trained psychoanalyst:

"The scientific psychologist in general and the psychoanalyst in particular must not only be able to freely dispose of empathy; they must also be able to abandon empathy. If they cannot go beyond empathy, they cannot form hypotheses and theories and thus ultimately cannot come up with explanations" (46)

But how does a psychoanalyst - just as much as any speaker, artist, performer - develop the ability to handle his or her own empathy with confidence? Kohut writes:

"[...] it is therefore the special task of teaching analysis to make the narcissistic positions of the training candidates more flexible in order to improve their empathy. Success in working through this area becomes evident when ego-dominance is obviously established, that is, when the candidate has acquired the free (autonomous) ability to adopt or even give up an empathetic attitude, according to his or her professional task"(47)

4.3 Ego-Dominance and Empathy

But how can one imagine this ego-dominance, the flexibility in one's own narcissistic positions, which both, the psychoanalyst as well as the high-wire circus artist, should have at their command?

Eventually the criterion by which the various forms of mutual embodiment can be distinguished is the respective participants’ emotional disposition. We all begin to experience mutual embodiment as infants, laying thus the foundation for our implicit relationship knowledge and our interactions repertoire.(48) But what is the position of the infantile agent, the infant, in a relationship? Its survival depends existentially on a benevolent dialogue with his caregiver. And depending on how happy the perceptual-action feedback is, his expressions can vary from a sovereign expression of his inner states to need-driven action, a desperate begging for redemption..

Unfortunately, it is not the case that our interaction repertoire is automatically updated as we grow up. Rather, the patterns learned in childhood continue with many adults and, as Halpern points out with a drastic example, sometimes lead to tragic results.(49)

"Engaged curiosity is especially important in emotionally distressing situations. Whether or not physicians try to empathize with their patients, they are in fact often deeply affected by the suffering and emotional difficulties they witness. [...] Physicians who are unaware of their own emotional state risk making poor decisions to alleviate their own distress. [...] As adults we are often unaware of how we reenact emotionally upsetting events. [...] Adults repeat their traumas just as children do, and in the intense setting of the hospital, it is not unusual for the whole treatment team to engage in the reenactment without being aware of it."(50)

In this sense, ego-dominance can thus only mean to actively develop our empathic abilities and to acquire modes of mutual embodiment in which we meet our counterpart in a self-determined way and at eye level.

4.4 Conclusion

Empathy is not an informational one-way road. The human capacity for dyadic, mutual embodiment is apparently anthropologically based(51) and it is normally a process that affects both participants alike. However, it is possible for agents to consciously control and sovereignly handle this process, and more so if they have developed ego-dominance, i.e. matured from existentially dependent participants to self-determined agents.

5 Touch and Change

But what about our initial question: How is it possible that, in a situation of deepest despair, a work of art has the power to give hope to a person – as it happened to James Rhodes(52)? How is it possible for a work of art to touch, to deeply move, perhaps even to heal a person?

5.1 Human Beings are Open Systems

As we have seen, empathy enables us to feel what others feel – but the phenomenon is not limited to that. If empathy is understood – just as Interaction Theory does – as our anthropologically based capacity for shared embodiment, then it is true to say that it opens up a channel of communication open in both directions, a channel through which people can communicate with each other, can touch each other and, yes, in this touch, also bring about change.(53)

For this to happen in a beneficial, healing way ideally both, but at least the agent that controls the process, should have ego-dominance:

"Physicians [or whoever wants to influence the empathic process in a healing way; KUS] need to cultivate curiosity about their own emotional reactions and about what they might be missing about the patient’s experience that, if better understood, might help them address the patient’s suffering."(54)

After all, what happens if, for example, a doctor and his patient meet without having done this preparatory work? Rogers develops a revealing hypothesis about the therapeutic process:

"The more the therapist perceives the client as a person rather than an object, the more the client will come to see himself as a person rather than an object"(55)

This means consequently: If people meet each other and enter into perceptual-action feedback without having done the appropriate preparatory work, they may risk facing each other as objects.

5.2 Human Beings are not Objects

Is that the problem? That a person perceives himself as an object? Because that is what he painfully experienced: That he was treated as an object?

Human beings are not objects, they're living organisms. But sometimes they are made objects by being treated as such:

"When science [...] transforms people into objects, it has yet another effect. Science, in its ultimate consequence, leads to manipulation."(56)

A person without ego-dominance, a doctor who is not aware of his own emotional states, risks making his patient the object of these emotional states while loosing sight of him as a human being. What he then performs on the patient is, even if done with the best healing intention, manipulation.

This problem is not limited to the doctor-patient relationship, Although it is used here as an exemplary case. It rather permeates our entire life. Even the caregiver who is unable to approach the infant in a benevolent way, to enter into a genuine dialogue with him and to allow him to express himself in a sovereign manner, makes him, this newborn open system human being, an object which finally will be driven by need and desperately beg for redemption.

5.3 Works of Art are Objects made by Human Hands

And a work of art? A work of art is certainly an object... but it is not an ordinary, everyday object like a cane for the blind or a piano.

So what happens when the open system human being is confronted with such a special object, a work of art? What is the difference between the encounter with a regular object compared to the encounter with a work of art? Who exactly, or what..., did James Rhodes meet when he first heard Bach's Charconne?

By definition, works of art are made by human hands, they emerge out of an intense process, condensed human experience manifested within them. In a certain way, one always encounters a human being in a work of art: the person who created it. Perhaps not necessarily a living, responding person, and certainly the encounter with a work of art – because of its inanimateness and objecthood - allows only one-sided embodiment. But works of art are nevertheless something completely different from the useful objects Fuchs speaks of, the cane for the blind or the piano. Works of art seem to possess a kind of aura, to breathe in a subtle way.

Or is it a human being, their creator, who breathes from them? Maybe it was this other human being that James Rhodes felt breathing through the Chaconne:

"When his first wife, the great love of his life, dies, he [Johann Sebastian Bach; KUS] writes a piece of music [, ...] a goddamn cathedral built in her memory. It is the Eiffel Tower among love songs. [...] Imagine absolutely everything you would want to say to a person you love if you knew he was going to die – even the things you could not put into words. Imagine you distilled all these words, feelings, emotions into the four strings of a violin and concentrated them into fifteen minutes excited to tearing. Imagine you somehow managed to build up this whole universe of love and sorrow in which we exist, put it into a musical form, write it down on paper and bestow it to the world. This is exactly what he has done, a thousand times, and this alone is enough to convince me that there is something greater and better in the world than my demons"(57)

5.4 Conclusion

As human beings, it is fundamental for us to connect with other people, to cross our own ego boundaries through our capacity for empathy, to form a common extended body with others and to evolve through this encounter.

But sometimes we find ourselves in existential dead ends, in which this path, the contact to a living counterpart, the Thou, is blocked. Eventually because our own situation is too terrible, too uncommunicable, perhaps because it was a person who hurt us, or maybe just because we lack a person we can or want to trust.

But even under these circumstances we still possess our capacity for empathy. And, if we are lucky, we might encounter a work of art. Non-human and yet human at the same time, an object, but a man-made object that speaks of human experience. Pain, grief, anger. Faith, hope. Joy. Love.

&"When I first heard the Chaconne... I was just seven years old. This music was so much deeper than anything I'd ever heard before. Everything had meaning in it, and everything in my life seemed meaningless then. So I grabbed this music and held it as tight as I could. It was proof that there is good in the world. The world could not merely be evil if this music existed."(58)

Perhaps one can define in this way what a work of art is: A work of art is an object that meets a human being in the same way only a human being can.

So that after the encounter this human being can then, perhaps, at some point, return to the other human beings.